Cubism from Scratch |

Use PROCESS, CREATIVE EXPERIMENTATION,

and DISCOVERY to foster Independent Creative

Work Habits. Students practice the

construction of knowledge.

Students to not imitate. They INNOVATE.

They do not work from examples.

They CREATE their own ideas.

by Marvin Bartel, Ed.D. © 2001

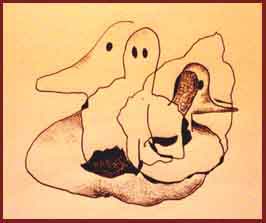

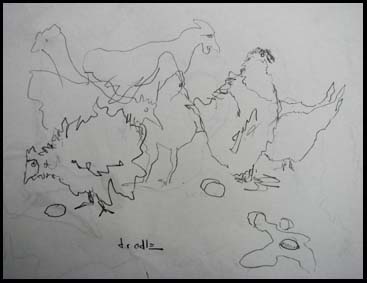

On the right

is a practice drawing using a three-dimensional paper

duck as a study.

Note that it has been drawn from different distances

and from different

views all within the same space.

The Objectives:

Practice observation drawing

Learn to compose shapes, lines, and colors

Learn about principles of composition including time, motion, emphasis,

and unity

Encourage creative divergent thinking and experimental work habits

Change habits of work and thinking

Foster a collaborative art studio atmosphere

Avoid becoming dependent on imitation and copywork

Avoid dependence on teacher demonstrations

Build self-confidence, natural curiosity, and focus

Encourage playfulness, connectedness, and

appreciation of nature and human history

Learn about an important art style (a way of seeing),

art history, art criticism, and aesthetics |

|

Age and Grade

Level

This is a good lesson for adults and children who have mastered

some abstract thinking ability. This lesson is best above second grade, but advanced kindergarten children enjoy it.

Teaching the Lesson

Do NOT show artwork or say the word cubism

until near the end of the lesson.

Do NOT demonstrate. Students learn by doing.

Have students practice from the motivations behind cubism without first seeing cubist images. Just like real artists are inventors, guide students to make discoveries, we help students discover cubism themselves. Celebrate with them. Help your students develop the habits of thinking used by highly creative people rather than teaching them to emulate artists by copying the mere look of their work. In order to do this, the teacher has studied cubism and has a working understanding of the theories and aesthetic motivations of historic cubism.

Traditionally, art historians have supposed that cubism represented a way of seeing our world from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, but now we have strong evidence that Braque and Picasso were influenced by the invention of motion pictures.

In 2007, there was a ground-breaking exhibition: Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism at the Pace Wildenstein in Brooklyn, New York, April 20 – June 23, 2007. Arne Glimcher and Bernice Rose invented and curated this very innovative exhibition that illustrates the influences of early motion picture film on minds of Picasso and Braque. Numerous art historians and painters have studied cubism for nearly 100 years and have never seen what has long seemed very obvious to Arne Glimcher. See sources below: #1 Micchelli, #2 Rose

Subject Matter

The teacher guides the students who learn

to set up a large still life in the middle of the room or several small

setups in the middle of their work tables. They bring in sporting

stuff, stuffed toys, musical instruments, some cloth, a few dry weeds,

and so on.

Depending of the season, some teachers bring large

sunflowers, grapes, gourds, squash, onions, eggplant, apples, and so forth

from the garden. Cut a few of these in half. Taste and smell

are excellent multi-sensory motivation.

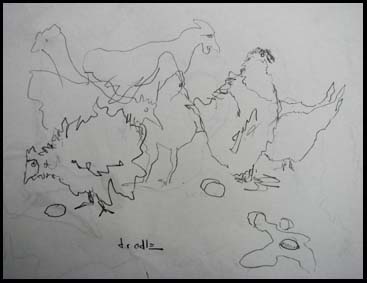

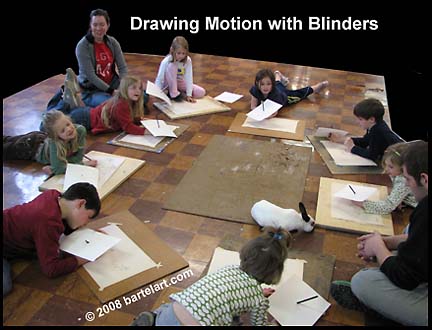

Another variation uses one or two student models that move according to teacher prompts to simulate a dance motion or an athletic action. In the variation below, two chickens move about while the class draws them.

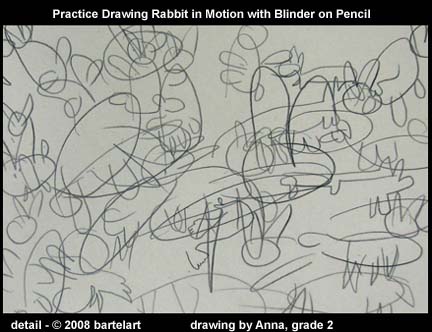

The pencil drawing on the right was made in the author's

adult drawing class. It is a practice observation drawing

of two chickens in motion drawn with the instructions to keep

drawing in the same space while the chickens are moving.

The instructions included the use of a blinder and

not looking at the paper while the pencil is in motion.

|

Drawing © Donn Odle 2008 |

Media

Distribute the materials before discussing

the process and giving drawing directions. This avoids disrupting

them when they are ready to start working.

|

Use any drawing media that students are

already familiar with. Otherwise use a warm up to familiarize students with the material. Select paper that is large enough for the

drawing tools and art media being used. For charcoal, pastels, oil

pastels and paints you could use 12 x 18 or larger. If they work

with drawing pencils, ink, ball point, or with small brushes, use a smaller

size so it does not take too long. This might depend on the the age and

prior experience of the students.

|

Instructions for

the Creative Process

-

If working at tables (observing a still-life or animal), encourage students to stand up while drawing

so they use arm motions instead finger motions. Ask them to begin

by selecting an interesting area in the setup and drawing very large so

things go off the edges. Cardboard viewfinders (or empty 35 mm slide

frames) are helpful in finding and sizing things. If it is a still-life, students work for few

minutes until the teacher has them move to a completely different position

and continue drawing the same objects on the same paper overlapping with

the drawing they started (or move the still-life).

-

Ask thinking questions and experiment questions. "What happens when you change the size or

scale when you change position? For those that have been drawing large: "What happens when you add small detail?"

For those that draw small: "What happens when you make the next part very much larger? How does it seem to move in and out in from your paper?" As much as posible, try to use open questions and "what if" questions rather than commands or suggestions.

-

Repeat drawing and moving to a new position

until the paper begins to fill with overlapping and transparent drawing

content.

-

After a few moves, invite students to slowly

walk around to see how other students have worked at the problem.

Affirm a diversity of approaches. Ask them a series of open questions to make them aware of motion and time. "How do the drawings suggest motion? Does anything in the drawings look farther away or closer to you? How does this happen? What things are repeated with variation? Can you see things about the drawings that move you into the drawing or away from the drawing? Do you see the effects of size change, of repetition, of gradation, and so on?"

-

As the paper begins to fill with overlapping

shapes, ask them what happens when you shade in and color the drawing to create an

overall pattern. What is the effect of gradations? What if they include some recognizable places

here and there? Can the evaluation is to be more on overall design and movement than

on realism? Ask them how they can make adjustments in the compositions

to achieve unity and harmony so that no one area becomes too dominant or

different than the whole.

In-Process Critique

-

When most of them appear to be nearly complete,

or when the first to finish feel they are done, have them all stop and

form groups of three.

- Prohibit negative responses. Encourage the use of questions that analyze and speculate.

-

Using six eyes instead of two, ask them to

look at each other's work and tell them what parts of their pictures they

notice first and why. What parts are showing most emphasis and what

parts show the least emphasis. Encourage every student to participate, to form questions, to describe what is noticed, to analyze, and to speculate.

- Ask them to discuss time and motion in the works.

-

They are not to use judgmental terms like

good or bad, just say what they see that shows the most and try to give

some reasons and explanations.

Continue the

Creative Process

If a student asks the teacher to tell

what to do next or if it is good enough, the teacher asks them a question

that gets them remember the process or to look at parts that they may have

missed. The teacher refrains from telling them what to do.

The teacher does not make a suggestion. The teacher gives them open choices rather than commands or directions.

The product is not supposed to have a certain look, but the students are

supposed to learn to make their own artistic choices based on criteria

the teacher gives. Resist the temptation to make specific

suggestions. Student thinking is cultivated better when the teacher honors the student ideas and does not do the thinking for the students.

Ending Critique

-

When they are done, have them post the work

for all to see. Discuss the work by again asking what they notice

first. Do not allow negative comments.

-

Follow the initial response by asking for

explanations of why they notice certain things. This is not

judging, it is describing and analyzing. If students miss things, the teacher asks about them. "Why do I see motion in this drawing?"

-

Sometimes it is also interesting to speculate

about the meaning of their pictures (interpretation). Making up titles

helps with this.

Art History

-

Show one or more example(s) of Georges

Braque

and or Picasso who invented cubism (use any general reference art history

book, library books on artists, slides, reproductions, posters, and/or

the internet). It is quite easy to print color pictures from the

web onto transparencies blanks made for ink jet printers (footnote web

sources). These can be shown in a class with an overhead projector if your

class does not have a computer projector to show them directly from the

web site. Kennedy - Rose

-

Ask them to speculate about the process the

artist(s) must have used to come up with their compositions. Ask

them how they think the artist was looking at the work.

-

Ask them to speculate about the reasons the

artist decided not to simply show a simple picture of the subject matter.

- Ask them to remember the way motion pictures move from clip to clip to tell a story.Kennedy - Rose

-

Explain the word Cubism and give a bit of

background on how innovative it was in the art world at the time it was

invented.

-

David Hockney

is a contemporary British artist who has played with these concepts by

using photography to make many pictures of of the same thing and putting

them all together in a composition that gives what he feels is a much more

realistic impression of how we perceive the world. He likens the

typical camera's photograph to the view of one eyed single impression Cyclops.

He claims that as humans we really see the world by mentally composing

reality from many visual impressions of a subject or scene.

Which is realism?

- Ask the students to write a short paragraph about what kind of art they think Picasso and Braque would invent if they where living today with cell phones, high speed Internet, and space travel.

Art in Everyday Life

How does all this connect to our lives

outside the art room? How is art and life connected? How are

the events of a day connected to each other and overlapping with each other?

Students are asked to make a list of everyday experiences that could be

represented cubistically.

-

Students are asked to make sketchbook entries

that cover a portion of a typical day all in one overlapping and transparent

composition. For example, each sketch combines several aspects of

the morning trip to school or the afternoon trip home.

-

Aesthetically, they are encouraged to reflect

on the differences in their feelings in the morning compared to their feelings

in the afternoon. How does is difference in feeling represented in

their cubist time sequence compositions. Could it be done with color

relationships, with size, with line type, or another device?

Review

Review is very efficient use of class

time. After reviewing something several times, it is much more apt to be remembered and used beneficially in another project. Sometimes there is a minute or two after cleanup time before

the bell rings. Even if the bell rings before a question is answered,

it is still good to raise the question.

-

Ask a review question.

-

Ask an art vocabulary question. What

does "emphasis" mean in a composition? What does "unity" mean?

What are the differences between "unity" and "harmony"?

-

How are artists similar to inventors?

-

Is cubism

more or less realistic than realism?

- How is the passage of time be shown in a drawing?

- Which is more beautiful, movement or symmetry and stability?

- What are the ways to show motion in a drawing?

- Which of you previous projects would be more fun if they included what we learned about motion today?

Review is even more effective if it is done

again at the beginning of the next session a day or more later. When a

teacher expects students to remember things from session to session, students

thinking habits are gradually trained to remember. They learn to expect that what is being learned has a purpose and it is to be incorporated into the next project. Ask questions that connect previous learning with today's questions and artwork.

To encourage creativity, pose questions that will be coming up in art class in the near future. I try to respond with enthusiasm to unexpected results--even when they are unexpected by me. "Wow! How did you do that?"

<><> END OF LESSON <><>

Credit:

This lesson was inspired by a similar lesson developed and taught by Judy

Wenig-Horswell, Associate Professor of Art, Goshen College.

Not enough time to do this lesson? Do not take shortcuts. Think of it as a unit that continues for as many sessions as are needed to do it well. Start each session with warm-up and review. Many more things are learned when we take the time to do something well. Teaching many short lessons leaves the impression that art is quick and easy. Art is not a bunch of products. It is a way of thinking and working that materializes and expresses ideas. Artist know that things worth doing take time and may require lots of experimentation.

SOURCES AND REFERENCES USED ABOVE - - - -Top of page

Kennedy, R. (2007) “When Picasso

and Braque Went to the Movies.” New York Times, April 15, 2007

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/15/arts/design/15kenn.html

[retrieved 12/14/2010]

Rose, C. (2007) “A

discussion about Picasso, Braque and Early Film in Cubism with Bernice Rose and Arne Glimcher in Art & Design” Friday, June 8, 2007 ” Charlie Rose, © 2010

http://www.charlierose.com/view/interview/8540 [retrieved 12/14/2010]

|

|

All Rights reserved © 2001, 2nd edition in 2008, by Marvin Bartel, Emeritus Professor of Art, Goshen College. All text and photo rights reserved.

You

are invited to link this page to your page. For permission to reproduce

or place this page on your site or to make printed copies, contact the author.

Marvin Bartel, Ed.D., Emeritus Professor of Art

Adjunct in Art Education

Goshen College, 1700 South Main St., Goshen IN 46526

Author Bio

updated: December 2008

A link to lessons on Cubism

from New Zealand

GOSHEN COLLEGE

Goshen, IN - USA |

|

|