Conductors

"The Big Cheese #4",

sculpture in welded aluminum by Bruce Gray.

A conductor is a material with a seemingly unlimited supply of charge carriers which are free to move. Implications:

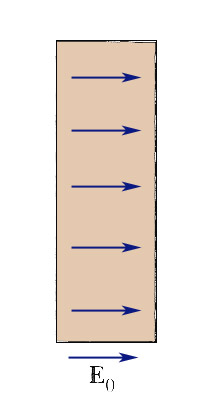

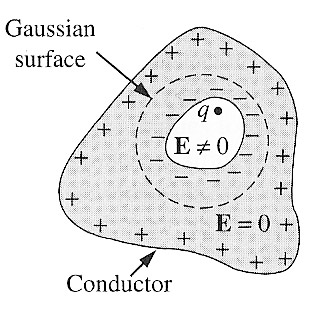

- $\myv E = 0$ inside a conductor. For, if $\myv E \ne 0$ somewhere,

then charges will move.

In an external field, charges will move until the net field inside vanishes.

- $\rho = 0$ everywhere inside a conductor. One of the fundamental properties of the electric field is $\myv \grad \cdot \myv E = \rho/\epsilon_0$.

- Any non-zero charge may only be found at the surface.

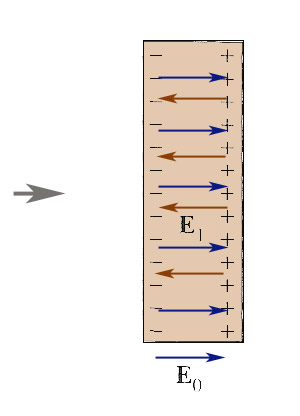

- A conductor is an equipotential: Consider any two points just barely inside the surface, where $\myv E=0$. $V(\myv b) -V(\myv a) = \int_{\myv a}^{\myv b} \myv E \cdot d \myv l=0$.

- $\myv E=-\myv\grad C$. The gradient of a function is always perpendicular to the contour lines / level surfaces / "equipotentials" of the potential function. Therefore $\myv E$ is always perpendicular to the surface (outside):

Another way to justify that "$\myv E$ is always perpendicular to the surface [outside a conducting surface]" is to note that...

- We found that for *any* surface (with or without charge) the parallel component of the electric field is continuous across the surface: $$\Rightarrow \myv E_{\parallel}^\text{above} = \myv E_{\parallel}^\text{below}.$$

- Since $\myv E =0$ below the surface, that implies that $\myv E_\parallel=0$ below the surface,

- So $\myv E_\parallel=0$ just above the surface as well.

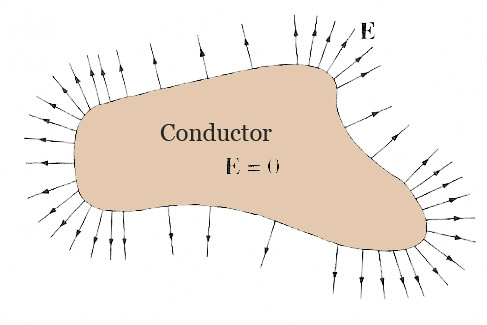

Induced charge

A charge outside a conductor gives rise to a non-zero electric field,

and this in turn induces a charge on a conductor (on the surface

of a conductor).

A charge inside a conductor also induces a charge on a conductor.

Example

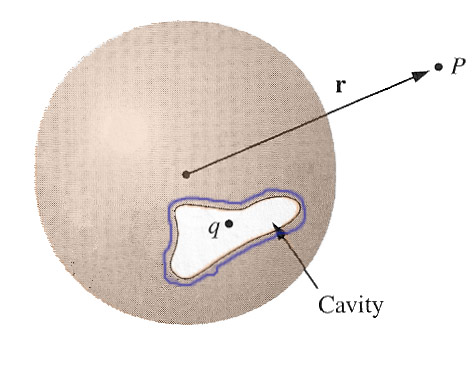

What's the electric field at a point $P$ at displacement $\myv r$ outside a spherical conductor with a charge inside the odd-shaped cavity shown?

The answer is... $\myv E = \frac{1}{4 \pi \epsilon_0}\frac{q}{r^2}\uv{r}$. Why?

Force on a conducting surface

When

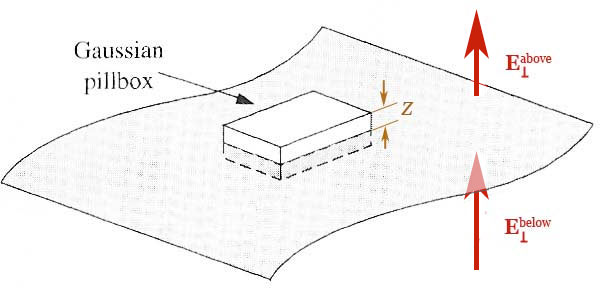

we looked at boundary conditions near an

accumulation of surface charge, we found that the perpendicular component

of the electric field is not continuous across some accumulation of surface

charge, but rather changes by

$$ E_{\perp}^{\text{above}} - E_{\perp}^{\text{below}}=\sigma

/ \epsilon_0.$$

...So applying Gauss' law, the field due to a surface charge density above an infinite plane has magnitude $$E_z=\frac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_0}.$$

To find the force on the small "pillbox" pictured we should multiply the charge in the box $\sigma A \times$ the electric field...but should we use the field above or below the box?

[For two point charges... distinguish between $\myv E$ and field of each particle...]

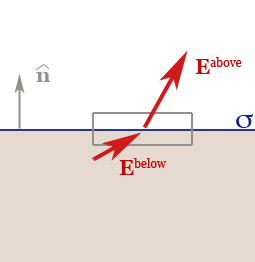

The electric field that we want to use in calculating the force is actually not either one, but rather that portion of the electric field which is due to charges "external" to the box. This will be continuous across the interface.

Part of the field is due to the surface charges themselves,

and we should subtract that part out. Indeed, close to the surface, the

field due to the surface charge $\myv E_\sigma$ is pointing normally away

from the surface both above and below. So, we could write the field above

and below as:

$$\myv E^{\text{above}} = \myv E^{\text{ext}}+\frac{\sigma}{2 \epsilon_0} \uv{n}$$

and

$$\myv E ^{\text{below}} = \myv E^{\text{ext}}-\frac{\sigma}{2 \epsilon_0} \uv{n}$$

Adding these two equations, $$\begineq \myv E^{\text{ext}} &= \frac{1}{2}(\myv E^{\text{above}} +\myv E^{\text{below}})\\ &= \myv E^{\text{ave}}.\endeq$$ On the surface of a conductor:

- the field in the conductor (below) has to be zero, and,

- the field just outside (above) has to be $\frac{\sigma}{\epsilon_0} \uv{n}$, and so

- $\myv E^{\text{ave}} = \frac{\sigma}{2 \epsilon_0} \uv{n}$, and so

- the force per unit area (pressure) is $F/A = qE^{\text{ave}}/A$ which is...

Or, since the field just outside the conductor is $E=\sigma/\epsilon_0$, $$P= \frac{\epsilon_0}{2} E^2.$$