Directional derivatives and the gradient

For a function $f(x,y)$, we have $f_x\equiv$ slope in the $x$-direction, and $f_y\equiv$ slope in the $y$-direction. What if we want the slope in some direction other than just the $x$- or $y$-direction?

Extended example

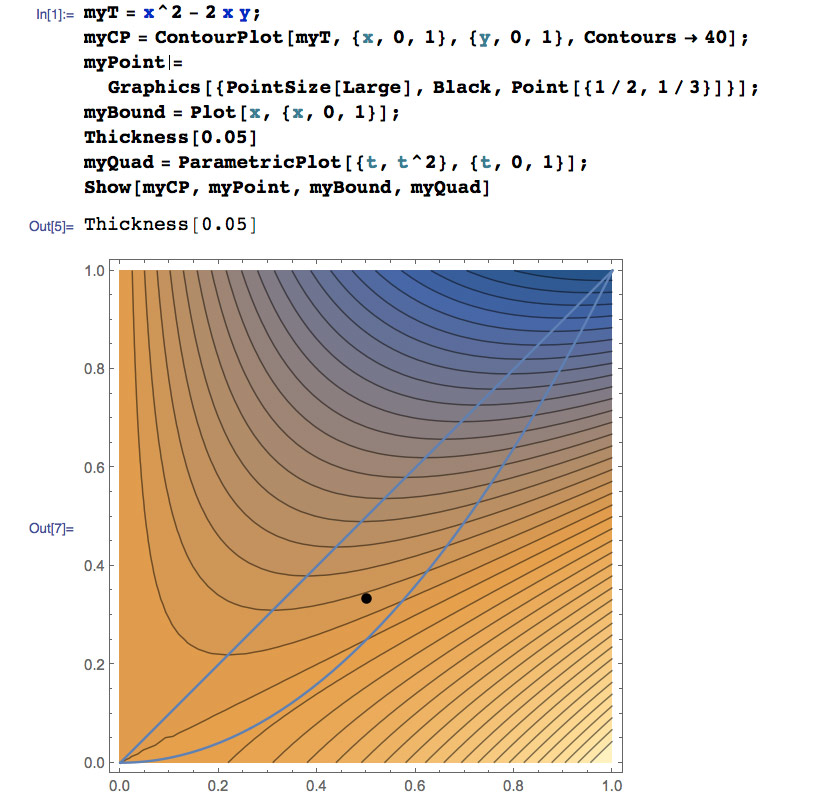

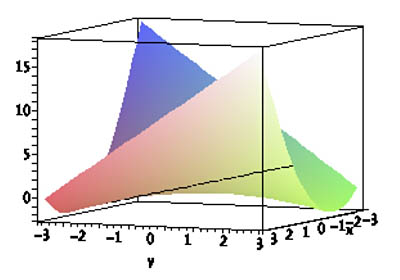

Consider the function $$\nonumber f(x,y)\equiv z(x,y)=x^2+xy$$

| How does the surface height, $z$, vary as you move along the line $$\nonumber x=t;\ \ y=2\ ?$$ |

|

| Height $z$ along the line

$$\nonumber x=t;\ \ y=2\ ?$$

$$\nonumber \left. \begin{eqnarray*} f(x,y)&=& x^2+xy\\ x&=&t\\ y&=&2 \end{eqnarray*} \}\Rightarrow z=t^2+2t$$ |

|

Compare

$$\nonumber \frac{dz}{dt}=2t+2$$

The chain rule...$$ \begineq \frac{dz}{dt} &=& \frac{\del z}{\del x} \frac{dx}{dt} + \frac{\del z}{\del y} \frac{dy}{dt}\\ &=&[2x+y](1)+[...](0)\\ &=&2x+2=2t+2\\ \endeq $$

| Height $z$ along the line $$\nonumber x=1;\ \ y=2+t\ ?$$ |

|

$$ \left. \begin{eqnarray*} f(x,y)&=& x^2+xy\\ x&=&1\\ y&=&2+t \end{eqnarray*} \} \Rightarrow z=1^2+(2+t)=3+t $$

Compare

$$\nonumber \frac{dz}{dt}=1$$

The chain rule...$$\nonumber \begineq \frac{dz}{dt} &=& \frac{\del z}{\del x} \frac{dx}{dt} + \frac{\del z}{\del y} \frac{dy}{dt}\\ &=& [...](0)+[x](1)= \left. x\right|^{x=1}=1 \endeq $$

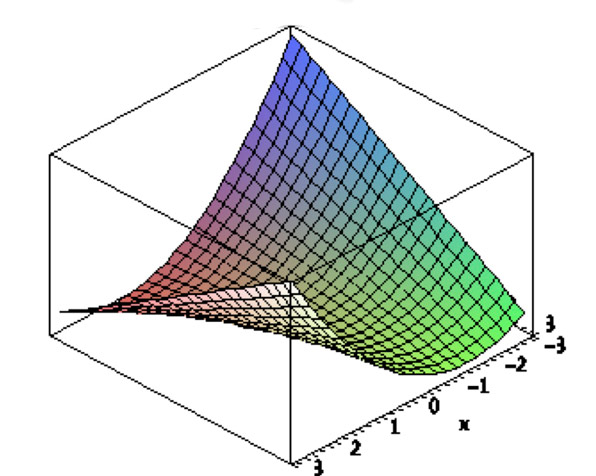

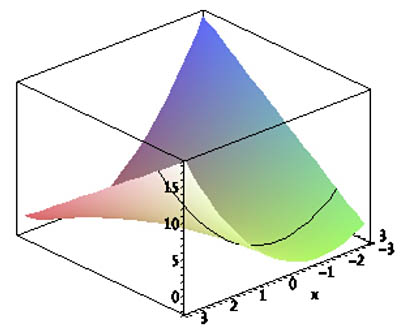

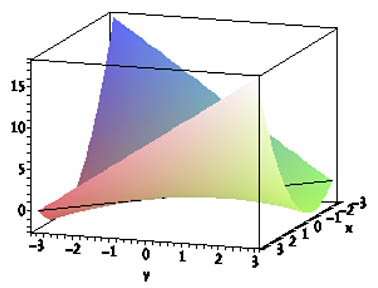

| Height $z$ along the line

$$\nonumber x=-3+t;\ \ y=-3+t\ ?$$

$t=0\Rightarrow (x,y)=(-3,-3)$ $t=6\Rightarrow (x,y)=(3,3)$ |

|

$$ \left. \begin{eqnarray*} f(x,y)&=& x^2+xy\\ x&=&-3+t\\ y&=&-3+t \end{eqnarray*} \} $$ $$ \begineq \Rightarrow z&=& (-3+t)^2+(-3+t)(-3+t)\\&=&2(-3+t)^2 \endeq $$

Compare

$$\nonumber \frac{dz}{dt}=4(-3+t)=4t-12$$

The chain rule...$$\nonumber \begineq \frac{dz}{dt} &=& \frac{\del z}{\del x} \frac{dx}{dt} + \frac{\del z}{\del y} \frac{dy}{dt}\\ &=&[2x+y](1)+[x](1)=3x+y\\ &=&3(-3+t)+(-3+t)=4t-12 \endeq $$

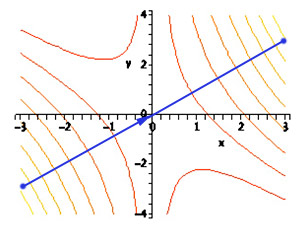

| Height $z$ along the line

$$\nonumber x=-3+t;\ \ y=3-t\ ?$$

$t=0\Rightarrow (x,y)=(-3,3)$ $t=6\Rightarrow (x,y)=(3,-3)$ |

|

$$\nonumber \left. \begin{eqnarray} f(x,y)&=& x^2+xy\\ x&=&-3+t\\ y&=&3-t \end{eqnarray} \} $$ $$ \begineq \Rightarrow z&=&(-3+t)^2+(3-t)(-3+t)\\ &=&(-3+t)^2-(-3+t)^2=0\endeq$$

Compare

$$\nonumber \frac{dz}{dt}=0$$

The chain rule...$$\nonumber \begineq \frac{dz}{dt} &=& \frac{\del z}{\del x} \frac{dx}{dt} + \frac{\del z}{\del y} \frac{dy}{dt}\\ &=&[2x+y](1)+[x](-1)=x+y\\ &=&(3-t)+(-3+t)=0\\ \endeq $$

Derivative in some arbitrary direction

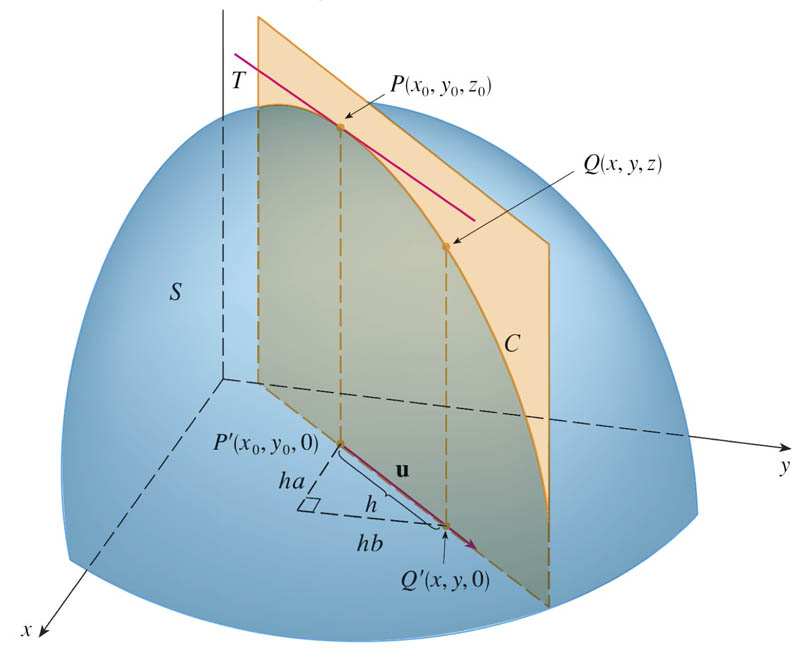

Let's say that we want the slope of the surface $z(x,y)$ in some arbitrary direction. Can we use the machinery that we used above--the chain rule and a line in the $x$- $y$-plane specified by a parameter $t$--to figure this out?

Let's say that the direction in the $x$- $y$-plane is specified by a unit vector $\uv u$. In terms of the angle $\theta$ that it makes with the $x$-axis, its components are

$$\uv u = \langle \uv u \cdot \uv i, \uv u \cdot \uv j\rangle=\langle \cos \theta, \sin \theta \rangle \equiv \langle a,b \rangle.$$

Let's say that the direction in the $x$- $y$-plane is specified by a unit vector $\uv u$. In terms of the angle $\theta$ that it makes with the $x$-axis, its components are

$$\uv u = \langle \uv u \cdot \uv i, \uv u \cdot \uv j\rangle=\langle \cos \theta, \sin \theta \rangle \equiv \langle a,b \rangle.$$

A vector function for the line $L$ running through $(x_0,y_0)$ which is parallel to $\uv u$ in terms of a parameter $h$ is $$\langle x(h), y(h)\rangle = \langle x_0+ha, y_0+hb \rangle.$$

Your book defines the directional directive of the function/surface $f(x,y)\equiv z$ at a particular point:

The directional derivative of $f$ at $(x_0,y_0)$ in the direction of a unit vector $\uv u=\langle a, b\rangle$ is $$D_{\uv u} f(x_0,y_0) \equiv \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x_0+ha,y_0+hb)-f(x_0,y_0)}{h}.$$

But we are in a position to find a slightly more general version, using the chain rule: $$\begineq D_{\uv u}z(x,y)&=&\left. \frac{dz}{dh}\right|^{\text{along }L}\\ &=& f_x \left. \frac{dx}{dh}\right|^{\text{along }L} + f_y \left. \frac{dy}{dh}\right|^{\text{along }L}\\ &=&f_x a + f_y b &=&\frac{\del f}{\del x} a + \frac{\del f}{\del y} b \endeq$$

Since $\uv u=a \uv i + b\uv j$ we could formally write this as a dot product of two vectors: $$D_{\uv u}f = \langle f_x,f_y \rangle \cdot \uv u\label{protog}.$$ That quantity in $\langle ... \rangle$ is so useful that we give it a name:

The gradient

If $f$ is a function of $x$ and $y$, then the gradient of $f$ is the vector function defined by $$ \myv \grad f \equiv \langle f_x(x,y),f_y(x,y) \rangle = \frac{\del f}{\del x} \uv i + \frac{\del f}{\del y}\uv j.$$

With this definition, the directional derivative can be written $$D_{\uv u} f = \myv \grad f (x,y) \cdot \uv u.$$

Maximizing $D_{\uv u}$

In what direction is the directional derivative a maximum?

The directional derivative is related to the gradient by $$D_{\uv u} f = \myv \grad f (x,y) \cdot \uv u.\nonumber $$

Using the properties of the dot product, $$D_{\uv u} = |\myv \grad f| |\uv u| \cos \theta =|\myv \grad f| \cos \theta $$ where $\theta$ is the angle between $\myv u$ and $\myv \grad f$.

Theorem Suppose $f$ is a differentiable function of two (or more) variables. The maximum value of $D_{\uv u}f(x,y,...)$ is $|\myv \grad f(x,y,...)|$ and it occurs when $\uv u$ has the same direction as the gradient vector $\myv \grad f(x,y,...)$.

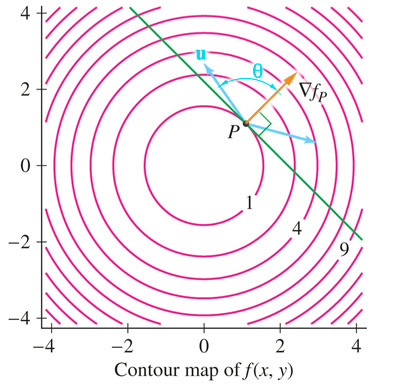

Graphical interpretation of the gradient

Assume that at a certain point $P$ the gradient of $f(x,y,...)$ exists, and $\myv \grad f_P \neq 0$. Let $\uv u$ be a unit vector making an angle $\theta$ with $\myv \grad f_P$. Then

$$D_{\uv u}

=|\myv \grad f| \cos \theta

.$$

- $\myv \grad f_P$ points in the direction of greatest possible increase from $P$.

- The length of the gradient vector, $|\myv \grad f_P|$, is the greatest slope away from $P$.

- $\myv \grad f_P$ does not point "uphill".

- $-\myv \grad f_P$ points in the direction of greatest possible decrease (the "fall line").

- When $\uv u$ makes an angle $\theta = \pm \pi/2$ with the gradient, it must be tangent to the level curve (contour line) or level surface running through $P$.

To do

- Heat-seeking kitten

Use this image for the "kitten" exercise: