Annotated bibliography

The annotated bibliography is a step along the way to the paper. Read about the paper in preparation for focussing the themes you'll write about in regard to your topic.

You will have already completed the "Summary of 3 resources" assignment.

In this more formal assignment you will:

- Summarize 4 sources. (You may include the 1 you previously summarized in the "3 Topics" assignment, if your topic now is the same as one from that assignment.)

- Each summary should include facts from your source and/or arguments your source makes that relate to your topic. A bulleted list is fine.

- Each summary should also include a paragraph or two of reflection (full sentences!) about this source. Some things to include: Summarize or synthesize the overall point of view; Any questions or discomfort that this source raises?; Thoughts about authority/reliability; What did you learn from this source?; Your evaluation of this source.

- In the reflection part, show me how your thinking is changing about your topic in light of the source.

- Write bibliographic information for each source in (your choice) either MLA or APA style.

For more info about source evaluation:

- Research: Evaluating sources in Diane Hacker

- Evaluating sources of information (Purdue OWL)

Recommended Sources, ranked by quality

By 'quality' I roughly mean results or writings which have been judged to be useful or original by others. The "others" might be recognized specialists in an area, the peer reviewers who go over articles submitted to scholarly journals, or editors of journals or publishing houses.

Quality is generally judged to be higher if the publisher of a resource does not have a direct commercial or political interest in the published source. That is, information published by government agencies are likely to be more trustworthy than advertisements paid for by a particular industry.

A rough hierarchy of sources by quality runs something like:

Highest quality, but an audience of specialists

You should find one resource in this category. GC Library's databases can help you find these.

-

Peer-reviewed articles in professional journals are perhaps the highest quality information sources, written by professional researchers who are funded by government or non-commercial sources. (They should not have a financial stake in the research, and professional journals often require a statement of financial interests of the authors.)

However, these articles also tend to be difficult to digest, and narrow in their focus: They use field-specific lingo, assume that the reader is already highly informed about recent research, and are frequently concerned with very specific sometimes technical concerns, rather than broader, interdisciplinary issues. - Articles or chapters written by a named, recognized specialist for a collection or specialized encyclopedia.

High quality, general audience

Sources written for a wide audience, both by researchers or by professional journalists, accountable to an editor and to fact checkers. Most of your resources should come from this category.

- Several top-quality, academic, peer reviewed journals also include articles, book reviews, and even summaries of the latest technical research (sometimes based on a research report published in the same issue!) but written for a general audience.

For example, Science magazine is a highly influential journal, as measured by its Impact Factor. It was ranked #22 on the 2023 Journal Impact Factor rankings, that some larger universities use to evaluate their researchers for promotions. Science labels their researcher-oriented content as Research articles. But they also have News, Perspectives, Insights, Features, Books sections that are written for a more general, science-interested audience.

The Goshen Library databases are also a good place to find these kind of articles. More examples:

Science, Nature, New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet

- News sources that are not journals, but have a long track record of covering science and/or environmental topics, with professional reporters, editors, and fact checkers.

Inside Climate News, Science News, New Scientist, Scientific American, Smithsonian, New York Times, NPR. Washington Post, The Economist, The New Yorker, The Atlantic

- Articles written for the public by scientists working for a government agency. e.g. agencies such as (hover to expand the acronyms...):

EPA, DOE including specific labs, such as NREL, EIA, NOAA, NASA (see their Vital Signs of the Planet website.

- articles written by professional journalists for general purpose publications, whose standards include fact checking and involvement of an editor such as

NYTimes, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, The New Yorker (click on a category such as Project Drawdown, Carbon Tracker, NRDC, UCS, WRI, Savannah Institute (agroforestry), ITDP (transportation and urban design), Citizen's Climate Lobby, American Lung Association

- Some colleges and universities have excellent news / education sites pitched at a general audience

Yale's e360 and Climate Connections, Harvard T.H. Chan school of public health's C-Change, MIT's Technology Review

- Books (which are *not* self published) generally involve an editor. By the nature of the economics of publishing, books are more likely to be pitched towards a general audience. You might dip in and out of a few books, but you may not have time to read too many books! You can look for reviews of books that you find interesting to see how others in the same field evaluate and critique the arguments of a book you're interested in.

- See also: IU Library's Climate Change research guides to websites and news sources.

- articles written by professional journalists for general purpose publications, whose standards include fact checking and involvement of an editor such as

Lower quality, but transparent process or authors

You will have perhaps 1 or 2 of these resources. But use them sparingly. Ideally you will use these as a way to find better quality resources. Try to find those higher-quality resources, and cite and rely primarily on those instead.

- Wikipedia - articles are subject to *informal* peer review.

- Press releases from academic institutions about the research that their faculty is carrying out.

- Writings, blog entries and web / Twitter postings by named people that relate to their association with a recognized organization (and / or cite higher quality sources that you can verify). E.g.

Lowest quality

These might supply you with ideas to investigate further, but should not be the sources that you rely on.

- Writings, blog entries, and web postings by named people, but with no obvious expertise or institutional connction.

- Articles on company websites, particular companies which have a financial interest in the content of the article. E.g. Information that you find on Tesla's website.

- Writings, blog entries, and web postings by people whose identity cannot be ascertained.

- Comments overheard from other tables at the dining hall.

- Ravings of the crazier members of your extended family.

Of course, you may use any of these as starting points of your research. But you should work your way back up the hierarchy of quality and eventually read, cite, and base your research on references closer to the high-quality, general audience category of the hierarchy.

It's fine to let a pop-culture reference on the radio pique your interest in something about, for example, hydrogen powered cars. You might familiarize yourself with hydrogen-fueled vehicles via Wikipedia or a quick Google search. Those articles often contain reference to higher quality resources. Preferentially, look up the higher-quality reference and read and cite that.

Resources on the web

In general, you should avoid non-edited, and non-peer reviewed articles on the web. However...

Sometimes you will find an article on the web which is a copy made available of a publication that appeared in print. The most important part to cite is the print reference for the article which will allow anyone to look in a library or an online database for the article. This has the *quality* of a print article. It is incidental that you found it via the web.

Sometimes you will find an article which does not have a print reference, but seems to be published by an academic researcher. In this case, see if you can find a non-web reference to the article, or another article by the same researcher on substantially the same topic. You can uncover some of these connections by using Google Scholar. Google Scholar is also useful for finding copies on the web of scholarly articles that appear to be behind a paywall.

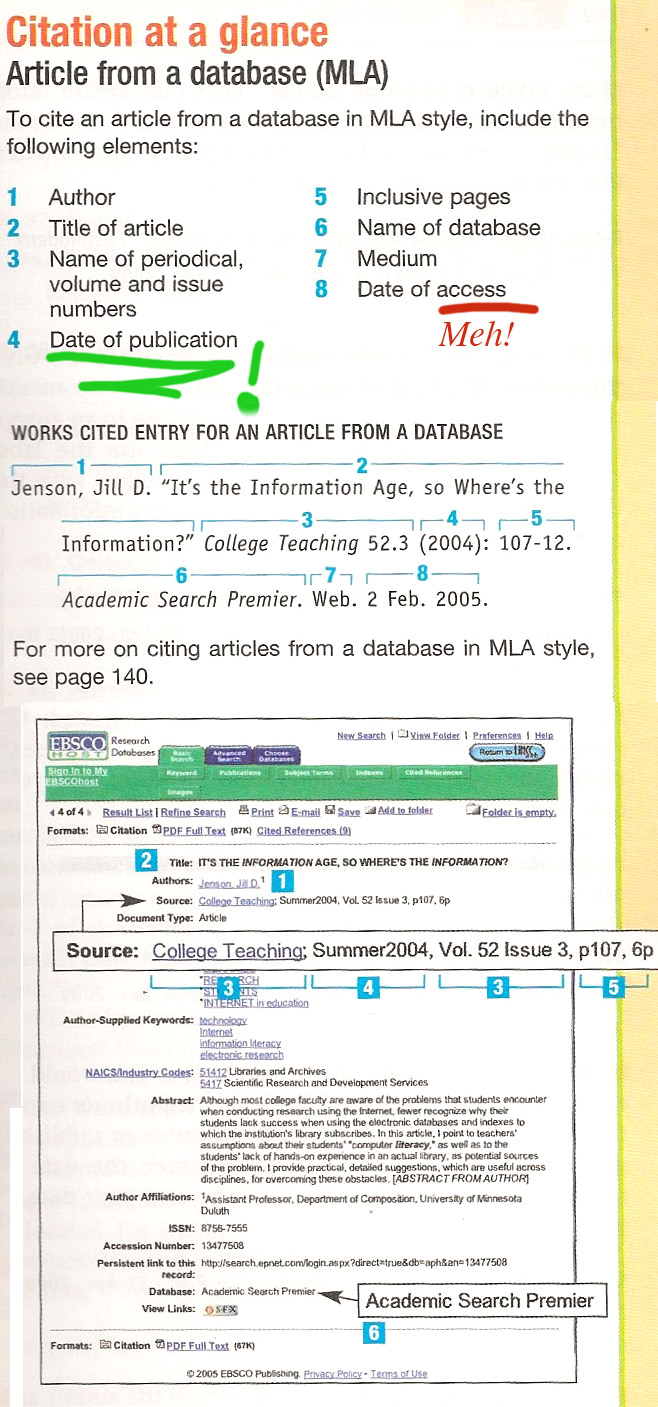

You will find articles from respectable journals via the web, in databases such as Academic Search Premier. In this case you should cite the journal reference first in your bibliography, and then include the database in which you found the article (according to either MLA or APA style).

My opinion is that the access date is completely unimportant if you're referring a published article, because the journal reference will not change, and does not depend on when you accessed the article. But, OK, OK, you *may* include it as the last element according to Hacker's guidelines about Work from a database,

Citation generators

- Any articles you can find via Google Scholar, you can also use their citation generator to get a properly formatted bibliography entry.

- Easybib.com allows you to type the URL of, for example, an online newspaper article, and it will try to harvest information from the web page and generate a bibliographic citation.